Intro to Filmmaking Part Three: Lists and Boards

If you’ve followed along with the first two parts of this series, we’ve been calling emphasis to the story you bring into a production, and to the team you assemble to bring that story to life. Many blogs skip over this next step and jump right into discussing production and post production. We’re going to be different and linger in pre production just a little bit longer, to discuss production planning by breaking down a script into shot lists and storyboards.

The artist in you should be excited about this step. Yes…on the surface it looks like a mountain of paperwork. But I’ll argue it’s giving you more chances to shoot your film before you ever whip out a camera! Scripting is writing. It’s kind of a different thing. You’re building a story narrative. All your rewrites focus on making the story better, and oftentimes you’re sidelining how your film will eventually look, to focus on the story you are trying to tell.

Writing isn’t shooting, it’s writing. But making shot lists and storyboards? Now that’s filming. By making shot lists and storyboards, you’re making decisions focused on the look and feel of your film, and you get to do it three times before you actually film.

This is a blessing. This is a vetting. This is an opportunity to make your film better.

THE SHOT LIST

A shot list can be complex. Or, it can be simple! Talk about it with your production management team. In other words, find out if it’s valuable to have lens focal length suggestions listed, or if perhaps you should specify whether a shot is on a tripod, handheld, or a drone shot. In its essence, a shot list is a setup checklist for the production team that focuses on the most important aspects to capture during filming.

There are many standardized suggestions for shot list formats that a rookie production team can turn to as a model, but do not be afraid of innovating or altering it.

In its essence, a shot list is a setup checklist for the production team that focuses on the most important aspects to capture during filming.

Usually, a shot list numbers out all shots that will be recorded, the scene number (which is derived from your scene slug in the script), and each iterative shot inside a scene. Naming conventions are required to make sense, and should be reflective of the needs of your unique production.

Sometimes, camera movement will be described in brief detail in addition to the scene event that is being captured. You will often see shot lists referencing talent in shot, dialogue, technical concerns or special effect considerations, wardrobe notes, set design notes, lighting notes, or whatever else might be specific to your film. If you’re filming at sea, perhaps you’re noting in your shot lists what happens in a studio location and what happens out on a naval location to balance expenses and crew burdens. Afford yourself some flexibility and uniqueness. Don’t stress shoehorning yourself and your production into a standard model. Bend the model to you.

With your sense of information that needs to be logged per shot, start at the beginning of your script and work your way to the very end. Break it out in single shot-by-single-shot events. Use that imagination of yours, and really see the edit unfold in your mind. Every time the camera hops around, or you have a visual break, that’s a new shot setup. (Or at least, that’s the starting point to get your mind around the concept).

Filmmakers have several shortcuts to use:

1. Wide to Close

When you go into actual production, the standard practice is to film wide, capture your scene in establishment, one or two angles (maybe three, whatever works for you), then move into a capture of your scene from medium angles or perhaps some OTS (“over the shoulder”) shots. And finally, close up shots. Start your scenes filming wide, and move in close. Rinse and repeat. Your shot list is well served to rely on this filming pattern. Wide, medium, close, and then insert shots. Wide, medium, close. When you get to your production scheduling this pattern helps you plan your locations, days, and where to schedule in your trick shots or technically demanding production days.

2. Continuous Take Dialogue

Most film shoots, even of budget, still orient production around a crew that keeps a single complex camera moving quickly. Multi-camera productions for dialogue filming are not frequent. But hey…if you can do it, do it! For the rest of us, the work-around goes like this:

Place the camera on your speaking talent for your dialogue scene. Just off camera is your other talent in the scripted conversation. Run the dialogue from top to bottom. Reverse your camera angle and capture the top to bottom of your second talent, and then edit together in post production. It’s a beginner’s common accident to believe that each line of dialogue is a contained take where an actor says one line, stop recording, turn the camera, record the response line, stop recording, turn the camera, etc. Instead, just take your dialogue scenes in big chunks from top to bottom with the camera on emphasis for each speaking individual, and bring those big footage pieces into editorial.

3. Insert Shots

An insert shot is a soft definition. It’s really any kind of camera angle shot that doesn’t rely heavily on the speaking or acting talent, and focuses more on objects or actions of significance. In a film like Apocalypse now, this may be as small as the rotating blades of a hotel room fan, or the spinning top in a high concept action film like Inception…but it’s those moments that take you into something specific the audience needs to see, or pulls you towards a mood or moment to gain perspective.

The advantage of Insert Shots is they aren’t terribly complex to film, they work well to carry the story from dialogue into action, and they are mostly designed as a way to inject variety into our wide to close and continuous take dialogue constructs.

Now. There’s more to your first imagining of the film than simply writing a shot list based on these handful of shortcuts. At some level, your imagination and expanded passion for filmmaking should be informing the creativity of your filming. These tactics are there to support your imagination with some reliable fallbacks.

Read books on cinematography, study films, go to lectures, and everything else that comes with learning a craft, to know all the creative shots you want to work in throughout your film. What we offer here is the barest bones of a starting framework. Great directors look at this foundation, then insist they can do better. You are challenged to think the same.

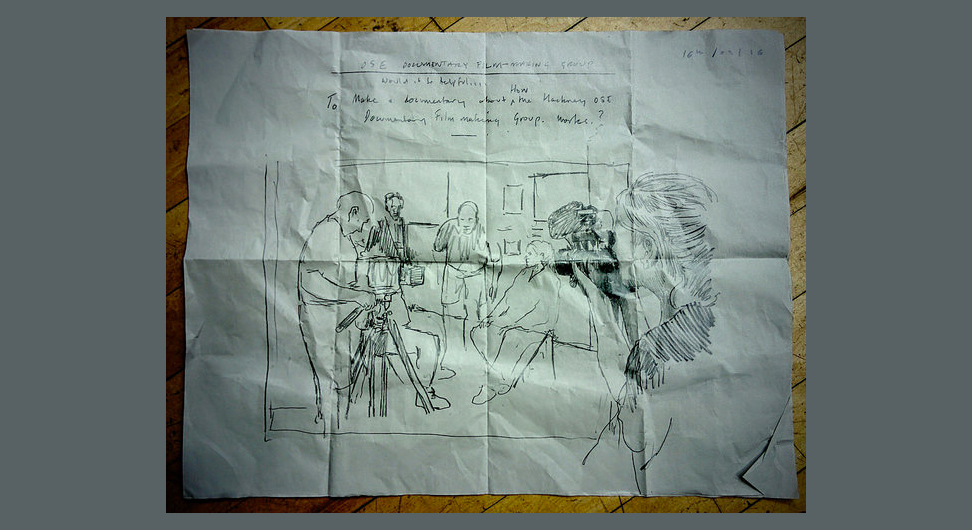

THE STORYBOARDS

So let’s talk about storyboards…before we talk about storyboards. This is an intimidating piece of the planning, because we’re filmmakers mostly because we can’t draw, and now one of the steps demands drawing! Well, sort of. There are many tactics at your disposal aside from drawing.

Think of it this way: the purpose of storyboards is to set your shot list into visuals.

You can go out with your phone and a friend to dummy act-out all your moments, then bring that into image software for layouts. Or, you can just go with stick figures and crude, broken perspective drawings. There are apps that allow you to move figures around. You can even download stock images, or steal still frames from films to map it out. It doesn’t matter. Storyboards are for you, and for a small number of team members who also need to work through the film’s vision in image form. Think of it this way: the purpose of storyboards is to set your shot list into visuals.

These tactics are used for films at all levels of production budgets. More money just allows you to use more expensive tools…but it’s always in service of the same objective: to see how the film works before you commit resources to filming. Each one of your shots is a storyboard card. Typically some amount of line gesturing is placed on each image representing movement from things in the scene or the camera. Each shot list line is a different image. You’re afforded some flexibility in repeating shot sequences like dialogue (no need to duplicate the exact same image 9 times for each take and reverse), or long sequences of still moments. But mostly you’re focusing on meticulous attention to visual flow. If you need to add or remove from your shot list to make the storyboards flow well, do it. You’re still trying to deliver the best story possible. Change what you must to make it better.

All this planning becomes a form of filming, because it’s challenging your imagination to prove itself as a real flow of storytelling imagery. Script-to-shot-list is essentially an effort to go through the granular details, and imagine what each single moment of your film will be like. Storyboarding, meanwhile, is essentially creating an overall visualization.

SO WHY DOES ALL OF THIS MATTER?

In a nutshell, your shot lists give your production leadership team a clear understanding of your story direction, rhythm of excitement, aesthetic style, and general flow. Your storyboards, meanwhile, should grant everyone a pretty good visual sense of the story you are about to film. Sure, you might have to go through a table read with the storyboards attached to really drive it home (depends on the art quality of your boards) but it really is a test model for your film.

If the storyboards don’t work, or your audience doesn’t connect with the story, then this is your chance to make changes with as much information in front of you as possible. Remember, story changes during production absolutely do happen, but it’s a lot less of a hassle to make changes during the storyboarding stage, than during filming.

If the shot list is your first filming of your piece, then the storyboard is the next revision level. You work it over and over and over until it’s right. In my experiences, you’ll tinker with the storyboards anywhere from 1 to 5 passthroughs, depending on story complexity. It takes some time to work through them all.

Take the time to do these specific steps right, and your production scheduling will become substantially easier, faster, and you’ll cut back on wasted time.

Our next piece will be all about building the schedule — aka, the production battle plan. We’ll get into how everything you’ve done before is leading you to scheduling, and how everything after is based on how effective your schedule is.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.