Intro to Filmmaking Part Two: The Minimum

What’s the bare minimum you need to make a film, and why are we asking like this? Filmmaking is hard, and when you’re first starting out, your resources and network are likely limited. We need to be reductive in order to better understand the mandatory minimum requirements. A big film will have big pockets and deep resources, no doubt, but what does it take when you’re working out of your living room?

It takes planning, it takes personal and family connections, and it takes time, all with a hardcore dedication to self-improvement. But first, it takes a team, and a team is more than two. We’re really talking about a bare minimum of three people to get anything done, and honestly…the more you can bring on board in dedicated roles, the better.

Today’s installment is all about these dedicated roles, what you need, and what you can grow into over time.

One human to play one character. Great…but as you read in part one, a good story is about character and conflict. Yes, there are some great solitary performers out there, but you usually have two characters driving that conflict with each other, or working together against an external problem.

So bare bones, a startup filmmaker is looking for two humans to perform on camera, with at least one more human operating the production. That’s a minimum team of three. You can’t do this alone–you can’t play all the roles and lead the production to success. Way too many variables to maintain and observe.

But let’s be thoughtful, too. Productions are orchestrations and events. They take logistics and planning, and as you move from just creating something towards creating something of value, you’ll need more humans to support the operation. Let’s take a look at some of the stand-out essential production roles.

The Writer

This human is dedicated to the story, and not just the first draft, but the first through the thirtieth draft. They’re the person facing the realities of production and drafting page-by-page rewrites hours before you film a scene. They keep wrenching and bending the story, safeguarding and abandoning components at will so that the final film can come together. Specific duties include: scriptwriting, re-writes, and (if permitted) a creative voice on set.

The Director

We’ve glorified this role in American culture, but at their core, a director is a middle manager. They maintain the project’s goals and final outcome, both in their head and in documentation. They are the project’s lead salesman, tasked with rallying people and money to the cause, and they’re the last one off set every night. The morale of the production, the tenor of the set, and the ability for a film to be successful lives and dies by the attitude and leadership skills of the director. They also must have enough technical know-how to lead their cinematographer in capturing the correct scene with the right lenses, communicating potential problems between the art department and wardrobe, and helping talent move through a scene with the right emotional flavor. They are the captain of the ship…but even then, it’s not a dictatorship. They’re decisionmakers and information synthesizers. Specific duties include: schedule management, performance direction, cinematic direction, and project cheerleader.

The Producer

What day will you film? What time will you show up? How many scenes will be filmed in a day? Does money need to be spent? Who brought lunch for everyone? These “back office” questions are answered before they’re asked by the producer. The human dedicated to this job spends a lot of time writing emails, pulling out every stop to bring the team together, and making sure that when the crew arrives to film on day one, there are no lingering problems or issues that cannot be solved. The relationship between producer and director is a tight one. These folks must trust each other and divide responsibilities for the good of the project. Specific duties include: budget management, business and legal compliance, securing talent and production, and fundraising.

The Cinematographer

The person who treats a camera like a musical instrument. There’s a mountain of specialized knowledge and skill required to capture a scene in movement and using that camera like a graceful tool–recording light and time with beauty and imagination. A good cinematographer knows when to work with a director in completing a vision, and knows when to push back against the impossible. Specific duties include: location scouting, comprehensive lens knowledge, technical acumen, and a keen eye for image composition through time and space.

The Audio Engineer

Humans digest sensory information in a hierarchy, and sound is processed in our minds in advance of visuals. Captured audio needs to be clean, clear, and consistent. The audio engineer is responsible for microphone placement, intense monitoring of every scene, and pushing the director for capturing and recording sounds that support the editorial process. The audio engineer is typically the only other human aside from the director authorized to cut or end a scene due to improper sound recordings. Specific duties include: monitoring location sound, foley, dialogue recording, and environmental audio capture.

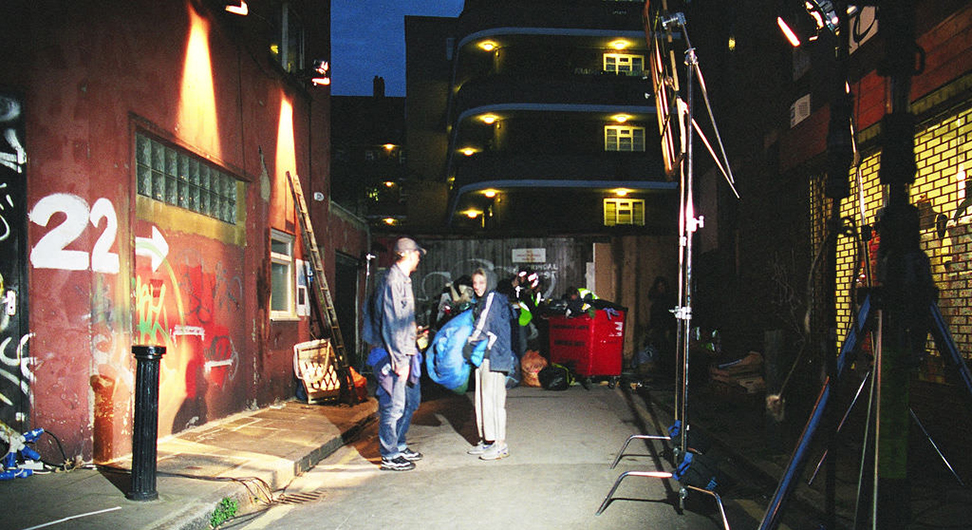

The Gaffer

Dedicated to the lighting of your scenes including coloring, shadows, fill, and everything else that makes what you want to put on camera visible to the naked eye and lens. The gaffer understands how color sets mood and can reveal important information. They also know when less is more, and when more is more. Sometimes talent just needs to be visible in the scene, and sometimes you need that dagger slash of light across the eyes. A skilled gaffer can accomplish both with ease. Specific duties include: lighting, electrical savvy, emotional tonality and action emphasis through light placement.

Art Director

110% dedicated to props and fill in your visual scene, the art director has an understanding of aesthetic balance, and knows how colors will either blend into or separate from your background. They re-arrange furniture and bring in extra details to deliver a scene. These are the people who transform warehouse floors into high-end urban lofts all through small adjustments and discussions with the cinematographer regarding angles. Their job is to make the scene sing. Specific duties include: scene dressing, props, all-around problem solving on set.

Hair/Makeup/Wardrobe

As a production scales in size and with budget, this role is often broken into several people, but for us at the shallow end of the pool, it’s usually just one individual dedicated to the complete and cohesive look of your talent on camera. They often pair closely with the gaffer and art director to ensure that talent looks their absolute best when inserted into the rest of the production machinations. Specific duties include: hair styling, makeup application, prosthetics, costumes and their sizings, and the use of color to communicate character traits.

The Production Assistant

These people tend to be treated the worst on set. Their job is to fill in the blanks for all the respective teams, and to leap into moving boxes, gear, or whatever else might happen. They are the backbone the entire production is built on, but also work as assistants to everyone. Great PA’s often rise in the ranks quickly, and it’s a wonderful starting point for anyone interested in field production. Just bring a thick skin to the game. Specific duties include: schedule management, equipment security, safety management, crew support, setting up and tearing down locations.

This bare bones list is just production. There’s a slew of post-production positions that often need to be filled as well, from the editor, to the FX, sound designer to composer among a handful more. But this above list is really what you’re striving to bring into your start-up productions for now.

The savvy reader will look at this list and find places of overlap, opportunities to condense roles and reduce the number of humans necessary. For example, it’s not rare for a director to also be a writer in indie productions, or perhaps your gaffer is also your art department head.

But as you condense roles and reduce the number of humans on a set, the amount of time it will take to set up each production shot goes up substantially.

Production is an economy of scale. It runs best when a lot of people get together knowing their roles. The scale can slide the other way too: just about every position can grow into full departments with leadership, assistants and crew.

That’s an important point. The considerations of a production team are fundamentally the same no matter what. The issue lies in the scope of your project.

Production is an economy of scale.

The biggest scale operations I’ve personally seen are reality TV shows–where an episode might only budget up to $40-$60k in an effort to cover two weeks of filming with a full crew on union rates. The smallest scale operations I’ve personally seen have been in my kitchen with a single lens DSLR, no audio, and workshop lights bounced off the ceiling.

The overlap between these two experiences is strong. In each situation you still need to light and block talent, think about your framing, ensure a compelling part of the story is being captured, adhere to a schedule, keep crew safe, etc.

Now with story and crew under our belts, we have the beginnings of some common language and priorities for the rest of the series. We can see our work decisions and choices through the lens of serving our story, and we can understand the scope of our production abilities via the depth and the breadth of our production team.

Charles Pearce manages Left Turn Only TV, a post production boutique studio tucked away in the East Austin production community as a member of The Swizzle Collective alongside 360 Studios.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.