The Seeker Part One: Life After Send

Until the dream, Nathan Raines had imagined that when he submitted his résumé to an online job post, his encapsulated career would land like a life preserver on some fatigued hiring manager’s desk.

Nathan’s precisely selected action-verbs would bloom in the glow of the office fluorescents, an unexpected burst of color amid the drab corporate environs. Maybe that’s the curse of the copywriter—unreasonable expectations of the power of words.

But now he worried there was another fate awaiting his applications. The dream was of a huge abyss into which all of his résumés disappeared, shuttled through the tubes of the internet and ejected into some cavernous tomb. Not just his résumés, but everyone’s résumés, a million or billion earnest pages fluttering down like autumn leaves. Nathan was old enough that he still imagined résumés as sheets of paper.

The paper piled up in huge alabaster drifts of optimistic objective statements and team-player assurance, an infinite string of routine tasks carefully crafted to sound significant, polished so defensively that the applicant’s own manager wouldn’t recognize the work.

Nathan was old enough that he still imagined résumés as sheets of paper.

The dream didn’t feel like his own. It looked like a film directed by Ridley Scott, set in a hopeless location with a dissonant soundtrack, his earnest ambitions crushed under uncountable almost-accurate synonyms, perfunctory duties dressed-up in stiff business attire, made/saved/achieved braggadocio deflated by passive language and typos that cursory proofreads failed to reveal.

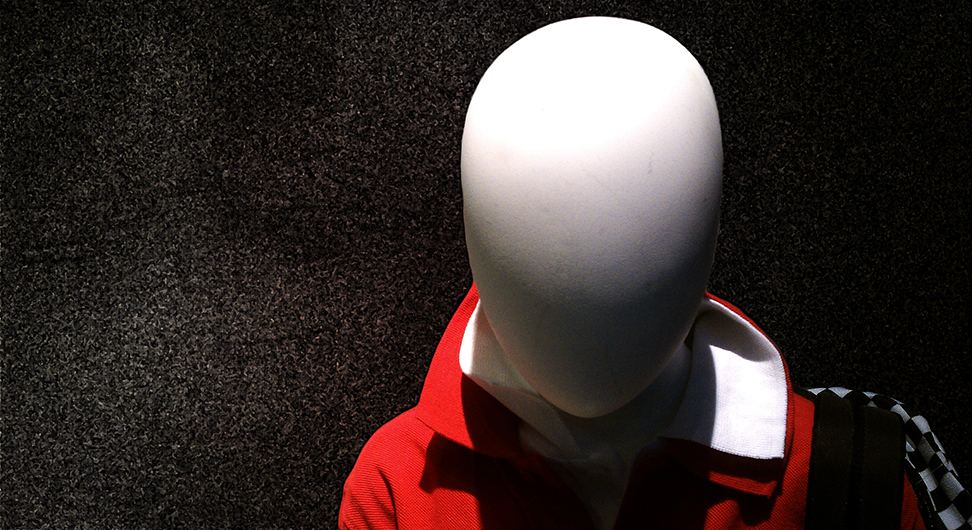

As he stared at the mountains of bullet-listed pages, Nathan realized how every person—the LinkedIn influencer whose experience reads like a history of employment buzzwords, the clever copywriter who uses 32 words to explain her love of brevity, the meticulous designer who insists his font choice will communicate more than the words written with it—was an equal there. Everyone’s paper ambassadors were indistinguishable in the darkness, their experience insufficiently search-engine-optimized, their talent deemed irrelevant by some technology they couldn’t predict.

He thought of the times he’d checked his email eight times a day, awaiting word that his résumé had reached its destination and magically massaged the soul of some overworked creative director, and he wondered how foolish this had been. He only applied for positions he felt exquisitely qualified for, so he always felt confident that his words would resonate. Now a different seed had been planted, an alternate reality, a slowly creeping suspicion that he was invisible under the crush of so many strangers’ aspirations.

In the past, when he didn’t get a reply to his electronic submission, he would concoct some plausible back-story to assuage his worries: maybe someone in the company had an inside track and posting the job was an HR requirement; maybe he’d applied late in the cycle and the weary screeners missed the nuance of his words; maybe the CFO had a nephew. Since the dream, those stories no longer offered reassurance. He’d seen the man behind the curtain. He wasn’t in Kansas anymore.

He’d seen the man behind the curtain. He wasn’t in Kansas anymore.

There was one particular moment of the dream that haunted him: deep in the shafts of the paper mines he’d seen workers toiling, shoveling the hopes and dreams of applicants into enormous bins that were then queued up to be destroyed at the moment the law allowed. Except he wasn’t seeing the workers from above—he was up close, as if he was there on the floor with them.

He watched a shovel scrape into the scattered reams then stop abruptly. He stooped to pick up a single sheet with a familiar pattern of white space and words on 90-pound ecru paper. In 16-point Arial at the top of the page he saw it: Nathan Raines. He let his shovel fall to the floor.

The horror jolted him into a waking state, frantically trying to sift the fiction from reality. He assured himself it was only a nightmare, just the stress of the job hunt finding an outlet in his subconscious. The abyss couldn’t be real. Companies need to find the right people—how would they do that if great candidates were being siphoned from the pile because they didn’t include the words “results-oriented” or “thought leader” in their résumés? People are too complex for such simple filters. It just wouldn’t make business sense.

At least that’s what Nathan told himself as he clicked send.

By day, William Reagan is a mild-mannered marketing copywriter stealthily sneaking clever wordplay into the most corporate of collateral—but at night, he’s a creative mischeivian bent on taking the shortest possible path to profound truths and/or preposterous lies. (Still mild-mannered then, too.)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.